Childhood Craniopharyngioma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Childhood Craniopharyngioma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]Skip to the navigationGeneral Information About Childhood Craniopharyngioma The PDQ childhood brain tumor treatment summaries are organized primarily according to the World Health Organization classification of nervous system tumors.[1,2] For a full description of the classification of nervous system tumors and a link to the corresponding treatment summary for each type of brain tumor, refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Brain and Spinal Cord Tumors Treatment Overview. Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer. Between 1975 and 2010, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[3] Childhood and adolescent cancer survivors require close follow-up because cancer therapy side effects may persist or develop months or years after treatment. (Refer to the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for specific information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors.) Primary brain tumors are a diverse group of diseases that together constitute the most common solid tumor of childhood. Brain tumors are classified according to histology, but tumor location and extent of spread are important factors that affect treatment and prognosis. Craniopharyngiomas are uncommon pediatric brain tumors. They are believed to be congenital in origin, arising from ectodermal remnants, Rathke cleft, or other embryonal epithelium, and often occur in the suprasellar region with an intrasellar portion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) imaging are used to diagnose craniopharyngiomas, but histologic confirmation is generally required before treatment. The treatment of newly diagnosed craniopharyngiomas may include a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and/or cyst drainage. The treatment of recurrent craniopharyngiomas depends on the initial treatment used. The 5-year and 10-year survival rates, regardless of treatment given, are higher than 90%. Incidence Craniopharyngiomas are relatively uncommon, accounting for about 6% of all intracranial tumors in children.[4,5,6] No predisposing factors have been identified. Anatomy

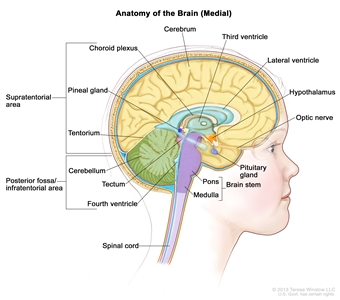

Anatomy of the inside of the brain, showing the pineal and pituitary glands, optic nerve, ventricles (with cerebrospinal fluid shown in blue), and other parts of the brain. The tentorium separates the cerebrum from the cerebellum. The infratentorium (posterior fossa) is the region below the tentorium that contains the brain stem, cerebellum, and fourth ventricle. The supratentorium is the region above the tentorium and denotes the region that contains the cerebrum.

Clinical Presentation Craniopharyngiomas occur in the region of the pituitary gland, and endocrine function may be affected. Additionally, their closeness to the optic nerves and chiasm may result in vision problems. Some patients present with obstructive hydrocephalus caused by tumor growth within the third ventricle. Rarely, tumors may extend into the posterior fossa, and patients may present with headache, diplopia, ataxia, and hearing loss.[7] Diagnostic Evaluation CT scans and MRI scans are often diagnostic for childhood craniopharyngiomas, with most tumors demonstrating intratumoral calcifications and a solid and cystic component. MRI of the spinal axis is not routinely performed. Craniopharyngiomas without calcification may be confused with other tumor types, such as germinomas or hypothalamic/chiasmatic astrocytomas, and biopsy or resection is required to confirm the diagnosis.[8] Apart from imaging, patients often undergo endocrine testing and formal vision examination, including visual-field evaluation. Prognosis Regardless of the treatment modality, long-term event-free survival is approximately 65% in children,[5,6] with 5-year and 10-year overall survival rates higher than 90%.[9,10,11,12] References:

-

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al., eds.: WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2007.

-

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al.: The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114 (2): 97-109, 2007.

-

Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.

-

Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, et al.: The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg 89 (4): 547-51, 1998.

-

Karavitaki N, Wass JA: Craniopharyngiomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 37 (1): 173-93, ix-x, 2008.

-

Garnett MR, Puget S, Grill J, et al.: Craniopharyngioma. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2: 18, 2007.

-

Zhou L, Luo L, Xu J, et al.: Craniopharyngiomas in the posterior fossa: a rare subgroup, diagnosis, management and outcomes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80 (10): 1150-4, 2009.

-

Rossi A, Cama A, Consales A, et al.: Neuroimaging of pediatric craniopharyngiomas: a pictorial essay. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 19 (Suppl 1): 299-319, 2006.

-

Muller HL: Childhood craniopharyngioma. Recent advances in diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Horm Res 69 (4): 193-202, 2008.

-

Müller HL: Childhood craniopharyngioma--current concepts in diagnosis, therapy and follow-up. Nat Rev Endocrinol 6 (11): 609-18, 2010.

-

Sanford RA, Muhlbauer MS: Craniopharyngioma in children. Neurol Clin 9 (2): 453-65, 1991.

-

Zacharia BE, Bruce SS, Goldstein H, et al.: Incidence, treatment and survival of patients with craniopharyngioma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Neuro Oncol 14 (8): 1070-8, 2012.

Histopathologic Classification of Childhood CraniopharyngiomaCraniopharyngiomas are histologically benign and often occur in the suprasellar region, with an intrasellar portion. They may be locally invasive and typically do not metastasize to remote brain locations; however, craniopharyngiomas may recur after initial therapy. Craniopharyngiomas are classified as one of the following: - Adamantinomatous: Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma is the most frequent type in children.[1] These tumors are typically composed of a solid portion formed by nests and trabeculae of epithelial tumor cells, with an abundance of calcification, and a cystic component that is filled with a dark, oily fluid. Wet keratin is also characteristic. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas are more locally aggressive than are papillary tumors and have a significantly higher rate of recurrence.[2] Activating beta-catenin gene mutations are found in virtually all adamantinomatous tumors.[3,4]

- Papillary: BRAF V600E mutations are observed in nearly all papillary craniopharyngiomas.[4] Papillary craniopharyngiomas occur primarily in adults.

References:

-

Karavitaki N, Wass JA: Craniopharyngiomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 37 (1): 173-93, ix-x, 2008.

-

Pekmezci M, Louie J, Gupta N, et al.: Clinicopathological characteristics of adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngiomas: University of California, San Francisco experience 1985-2005. Neurosurgery 67 (5): 1341-9; discussion 1349, 2010.

-

Sekine S, Shibata T, Kokubu A, et al.: Craniopharyngiomas of adamantinomatous type harbor beta-catenin gene mutations. Am J Pathol 161 (6): 1997-2001, 2002.

-

Brastianos PK, Taylor-Weiner A, Manley PE, et al.: Exome sequencing identifies BRAF mutations in papillary craniopharyngiomas. Nat Genet 46 (2): 161-5, 2014.

Stage Information for Childhood CraniopharyngiomaThere is no generally applied staging system for childhood craniopharyngiomas. For treatment purposes, patients are grouped as having newly diagnosed or recurrent disease. Treatment Option Overview for Childhood CraniopharyngiomaTable 1 describes the treatment options for newly diagnosed and recurrent childhood craniopharyngioma. Table 1. Treatment Options for Childhood Craniopharyngioma| Treatment Group | Treatment Options |

|---|

| Newly diagnosed childhood craniopharyngioma | Radical surgery with or without radiation therapy | | Subtotal resection with radiation therapy | | Primary cyst drainage with or without radiation therapy | | Recurrent childhood craniopharyngioma | Surgery | | Radiation therapy, including radiosurgery | | Intracavitary instillation of radioactive phosphorus P 32, bleomycin, or interferon-alpha, for those with cystic recurrences | | Systemic interferon | Newly Diagnosed Childhood Craniopharyngioma TreatmentTreatment Options for Newly Diagnosed Childhood Craniopharyngioma There is no consensus on the optimal treatment for newly diagnosed craniopharyngioma, in part because of the lack of prospective randomized trials that compare the different treatment options. Treatment is individualized on the basis of factors that include the following: - Tumor size.

- Tumor location.

- Extension of the tumor.

- Potential short-term and long-term toxicity.

Treatment options for newly diagnosed childhood craniopharyngioma include the following: - Radical surgery with or without radiation therapy.

- Subtotal resection with radiation therapy.

- Primary cyst drainage with or without radiation therapy.

Radical surgery with or without radiation therapy It may be possible to remove all visible tumor and achieve long-term disease control because these tumors are histologically benign.[1][Level of evidence: 3iA]; [2][Level of evidence: 3iiiB]; [3][Level of evidence: 3iiiC] A 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate of about 65% has been reported.[4] Gross-total resection is often technically challenging because the tumor is surrounded by vital structures, including the optic nerves and chiasm, the carotid artery and its branches, the hypothalamus, and the third cranial nerve. These structures may limit the ability to remove the entire tumor. Many surgical approaches have been described, and the choice is determined by tumor size, location, and extension. Radical surgical approaches include the following: If the surgeon indicates that the tumor was not completely removed or if postoperative imaging reveals residual craniopharyngioma, radiation therapy may be recommended to prevent early progression.[11][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiii] Periodic surveillance using magnetic resonance imaging is performed for several years after radical surgery because of the possibility of tumor recurrence. Subtotal resection with radiation therapy The goal of limited surgery is to establish a diagnosis, drain any cysts, and decompress the optic nerves. No attempt is made to remove tumor from the pituitary stalk or hypothalamus in an effort to minimize the late effects associated with radical surgery.[9] The surgical procedure is often followed by radiation therapy, with a 5-year PFS rate of about 70% to 90%[4,12]; [13][Level of evidence: 3iDiii] and 10-year overall survival rates higher than 90%.[14][Level of evidence: 3iiA]; [15][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiii] Conventional radiation therapy is fractionated external-beam radiation, with a recommended dose of 54 Gy to 55 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions.[16] Transient cyst enlargement may be noted soon after radiation therapy but generally resolves without further intervention.[17][Level of evidence: 3iDiv] A systematic review of 109 reports that described extent of resection found that subtotal resection plus radiation therapy was associated with rates of tumor control similar to those for gross-total resection. It was also reported that both approaches were associated with higher PFS rates than was subtotal resection alone.[15][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiii] Surgical complications with a subtotal resection are less likely than with radical surgery. Complications of radiation therapy include the following: - Loss of pituitary hormonal function.

- Cognitive dysfunction.

- Development of late strokes and vascular malformations.

- Delayed blindness.

- Development of second tumors.

- Malignant transformation of the primary tumor within the radiation field (rare).[18,19]

Newer radiation technologies such as intensity-modulated proton therapy may reduce scatter during whole-brain and whole-body irradiation and result in the sparing of normal tissues. When these highly conformal radiation treatments are employed, interim imaging is commonly performed to detect changes in cyst volume, with treatment plans modified as appropriate.[20,21,22] It is unknown whether such technologies result in reduced late effects from radiation.[13,21,22,23] Tumor progression remains a concern, and it is usually not possible to repeat the radiation dose. In selected cases, stereotactic radiation therapy can be delivered as a single large dose of radiation to a small field.[24][Level of evidence: 3iC] Proximity of the craniopharyngioma to vital structures, particularly the optic nerves, limits this to small tumors within the sella.[25][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiii] Primary cyst drainage with or without radiation therapy For large cystic craniopharyngiomas, particularly in children younger than 3 years and in those with recurrent cystic tumor after initial surgery, stereotactic or open implantation of an intracystic catheter with a subcutaneous reservoir may be a valuable alternative treatment option. Benefits include temporary relief of fluid pressure by serial drainage, and in some cases, for intracystic instillation of sclerosing agents as a means to postpone or obviate radiation treatment. This procedure may also allow the surgeon to use a two-staged approach: first draining the cyst via the implanted catheter, to relieve pressure and complicating symptoms; and then later resecting the tumor or employing radiation therapy.[26] References:

-

Mortini P, Losa M, Pozzobon G, et al.: Neurosurgical treatment of craniopharyngioma in adults and children: early and long-term results in a large case series. J Neurosurg 114 (5): 1350-9, 2011.

-

Elliott RE, Hsieh K, Hochm T, et al.: Efficacy and safety of radical resection of primary and recurrent craniopharyngiomas in 86 children. J Neurosurg Pediatr 5 (1): 30-48, 2010.

-

Zhang YQ, Ma ZY, Wu ZB, et al.: Radical resection of 202 pediatric craniopharyngiomas with special reference to the surgical approaches and hypothalamic protection. Pediatr Neurosurg 44 (6): 435-43, 2008.

-

Yang I, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, et al.: Craniopharyngioma: a comparison of tumor control with various treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E5, 2010.

-

Locatelli D, Massimi L, Rigante M, et al.: Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for sellar tumors in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 74 (11): 1298-302, 2010.

-

Chivukula S, Koutourousiou M, Snyderman CH, et al.: Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery in the pediatric population. J Neurosurg Pediatr 11 (3): 227-41, 2013.

-

Sands SA, Milner JS, Goldberg J, et al.: Quality of life and behavioral follow-up study of pediatric survivors of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg 103 (4 Suppl): 302-11, 2005.

-

Müller HL, Gebhardt U, Teske C, et al.: Post-operative hypothalamic lesions and obesity in childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational prospective trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2000 after 3-year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol 165 (1): 17-24, 2011.

-

Elowe-Gruau E, Beltrand J, Brauner R, et al.: Childhood craniopharyngioma: hypothalamus-sparing surgery decreases the risk of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98 (6): 2376-82, 2013.

-

Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al.: Treatment-related morbidity and the management of pediatric craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr 10 (4): 293-301, 2012.

-

Lin LL, El Naqa I, Leonard JR, et al.: Long-term outcome in children treated for craniopharyngioma with and without radiotherapy. J Neurosurg Pediatr 1 (2): 126-30, 2008.

-

Winkfield KM, Tsai HK, Yao X, et al.: Long-term clinical outcomes following treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56 (7): 1120-6, 2011.

-

Merchant TE, Kun LE, Hua CH, et al.: Disease control after reduced volume conformal and intensity modulated radiation therapy for childhood craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 85 (4): e187-92, 2013.

-

Schoenfeld A, Pekmezci M, Barnes MJ, et al.: The superiority of conservative resection and adjuvant radiation for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurooncol 108 (1): 133-9, 2012.

-

Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al.: A systematic review of the results of surgery and radiotherapy on tumor control for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst 29 (2): 231-8, 2013.

-

Kiehna EN, Merchant TE: Radiation therapy for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E10, 2010.

-

Shi Z, Esiashvili N, Janss AJ, et al.: Transient enlargement of craniopharyngioma after radiation therapy: pattern of magnetic resonance imaging response following radiation. J Neurooncol 109 (2): 349-55, 2012.

-

Ishida M, Hotta M, Tsukamura A, et al.: Malignant transformation in craniopharyngioma after radiation therapy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol 29 (1): 2-8, 2010 Jan-Feb.

-

Aquilina K, Merchant TE, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al.: Malignant transformation of irradiated craniopharyngioma in children: report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg Pediatr 5 (2): 155-61, 2010.

-

Winkfield KM, Linsenmeier C, Yock TI, et al.: Surveillance of craniopharyngioma cyst growth in children treated with proton radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73 (3): 716-21, 2009.

-

Beltran C, Roca M, Merchant TE: On the benefits and risks of proton therapy in pediatric craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82 (2): e281-7, 2012.

-

Bishop AJ, Greenfield B, Mahajan A, et al.: Proton beam therapy versus conformal photon radiation therapy for childhood craniopharyngioma: multi-institutional analysis of outcomes, cyst dynamics, and toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 90 (2): 354-61, 2014.

-

Boehling NS, Grosshans DR, Bluett JB, et al.: Dosimetric comparison of three-dimensional conformal proton radiotherapy, intensity-modulated proton therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for treatment of pediatric craniopharyngiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82 (2): 643-52, 2012.

-

Kobayashi T: Long-term results of gamma knife radiosurgery for 100 consecutive cases of craniopharyngioma and a treatment strategy. Prog Neurol Surg 22: 63-76, 2009.

-

Hasegawa T, Kobayashi T, Kida Y: Tolerance of the optic apparatus in single-fraction irradiation using stereotactic radiosurgery: evaluation in 100 patients with craniopharyngioma. Neurosurgery 66 (4): 688-94; discussion 694-5, 2010.

-

Schubert T, Trippel M, Tacke U, et al.: Neurosurgical treatment strategies in childhood craniopharyngiomas: is less more? Childs Nerv Syst 25 (11): 1419-27, 2009.

Recurrent Childhood Craniopharyngioma TreatmentTreatment Options for Recurrent Childhood Craniopharyngioma Recurrence of craniopharyngioma occurs in approximately 35% of patients regardless of primary therapy.[1] Treatment options for recurrent childhood craniopharyngioma include the following: - Surgery.

- Radiation therapy, including radiosurgery.

- Intracavitary instillation of radioactive phosphorus P 32 (32P), bleomycin, or interferon-alpha, for those with cystic recurrences.

- Systemic interferon.

The management of recurrent craniopharyngioma is determined largely by previous therapy. Repeat attempts at gross-total resections are difficult, and long-term disease control is less often achieved.[2][Level of evidence: 3iiiDi] Complications are more frequent than with initial surgery.[3][Level of evidence: 3iiiDi] If not previously employed, external-beam radiation therapy is an option, to include consideration of radiosurgery in selected circumstances.[4][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiii] Cystic recurrences may be treated with intracavitary instillation of varying agents via stereotactic delivery or placement of an Ommaya catheter.[5] These agents have included radioactive 32P or other radioactive compounds,[6,7,8]; [9][Level of evidence: 2A], bleomycin,[10]; [11][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiii] or interferon-alpha.[12]; [13][Level of evidence: 3iiiB] These strategies have been found to be useful in certain cases, and a low risk of complications has been reported. However, none of these approaches have shown efficacy against solid portions of the tumor. Although systemic therapy is generally not utilized, a small series has shown that the use of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alpha-2b to manage cystic recurrences can result in durable responses.[14][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiii] Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Recurrent Childhood Craniopharyngioma The following is an example of a national and/or institutional clinical trial that is currently being conducted. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website. - PBTC-039 (NCT01964300) (Peginterferon Alfa-2b in Treating Younger Patients With Craniopharyngioma That is Recurrent or Cannot Be Removed By Surgery): This is a phase II clinical trial evaluating how well peginterferon alfa-2b works in treating children with craniopharyngioma that is recurrent or cannot be removed by surgery. This trial follows a small (N = 5) single-institution experience with peginterferon alfa-2b, in which prolonged complete responses were observed in some patients.[14]

References:

-

Yang I, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, et al.: Craniopharyngioma: a comparison of tumor control with various treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E5, 2010.

-

Vinchon M, Dhellemmes P: Craniopharyngiomas in children: recurrence, reoperation and outcome. Childs Nerv Syst 24 (2): 211-7, 2008.

-

Jang WY, Lee KS, Son BC, et al.: Repeat operations in pediatric patients with recurrent craniopharyngiomas. Pediatr Neurosurg 45 (6): 451-5, 2009.

-

Xu Z, Yen CP, Schlesinger D, et al.: Outcomes of Gamma Knife surgery for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurooncol 104 (1): 305-13, 2011.

-

Steinbok P, Hukin J: Intracystic treatments for craniopharyngioma. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E13, 2010.

-

Julow J, Backlund EO, Lányi F, et al.: Long-term results and late complications after intracavitary yttrium-90 colloid irradiation of recurrent cystic craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery 61 (2): 288-95; discussion 295-6, 2007.

-

Barriger RB, Chang A, Lo SS, et al.: Phosphorus-32 therapy for cystic craniopharyngiomas. Radiother Oncol 98 (2): 207-12, 2011.

-

Maarouf M, El Majdoub F, Fuetsch M, et al.: Stereotactic intracavitary brachytherapy with P-32 for cystic craniopharyngiomas in children. Strahlenther Onkol 192 (3): 157-65, 2016.

-

Kickingereder P, Maarouf M, El Majdoub F, et al.: Intracavitary brachytherapy using stereotactically applied phosphorus-32 colloid for treatment of cystic craniopharyngiomas in 53 patients. J Neurooncol 109 (2): 365-74, 2012.

-

Linnert M, Gehl J: Bleomycin treatment of brain tumors: an evaluation. Anticancer Drugs 20 (3): 157-64, 2009.

-

Hukin J, Steinbok P, Lafay-Cousin L, et al.: Intracystic bleomycin therapy for craniopharyngioma in children: the Canadian experience. Cancer 109 (10): 2124-31, 2007.

-

Ierardi DF, Fernandes MJ, Silva IR, et al.: Apoptosis in alpha interferon (IFN-alpha) intratumoral chemotherapy for cystic craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst 23 (9): 1041-6, 2007.

-

Cavalheiro S, Di Rocco C, Valenzuela S, et al.: Craniopharyngiomas: intratumoral chemotherapy with interferon-alpha: a multicenter preliminary study with 60 cases. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E12, 2010.

-

Yeung JT, Pollack IF, Panigrahy A, et al.: Pegylated interferon-α-2b for children with recurrent craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg Pediatr 10 (6): 498-503, 2012.

Late Effects in Patients Treated for Childhood CraniopharyngiomaQuality-of-life issues are important in this group of patients and are difficult to generalize because of the various treatment modalities. Late effects of treatment for childhood craniopharyngioma include the following: - Behavioral issues and memory deficits. Although intelligence quotient is usually maintained, behavioral issues and memory deficits attributed to the frontal lobe and hypothalamus commonly occur.[1] Patients with hypothalamic involvement showed impairment in memory and executive functioning.[2]

- Vision loss.

- Endocrine abnormalities. Endocrine abnormalities result in the almost universal need for life-long endocrine replacement with multiple pituitary hormones.[3,4,5][Level of evidence: 3iiiC] A report indicated that adults, despite being treated with long-term growth hormone replacement after childhood onset craniopharyngioma involving the hypothalamus, were at increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease.[6]

- Obesity, which can be life-threatening, and the development of metabolic syndrome, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.[7,8]

- Vasculopathies and stroke. Vasculopathies and subsequent strokes may result from local irradiation.[9,10] One cross-sectional cohort study observed a trend suggesting that long-term growth hormone replacement may reduce the risk of stroke.[10]

- Subsequent neoplasms. Subsequent neoplasms may result from local irradiation.[9]

Refer to the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for specific information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors. References:

-

Winkfield KM, Tsai HK, Yao X, et al.: Long-term clinical outcomes following treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56 (7): 1120-6, 2011.

-

Özyurt J, Thiel CM, Lorenzen A, et al.: Neuropsychological outcome in patients with childhood craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic involvement. J Pediatr 164 (4): 876-881.e4, 2014.

-

Vinchon M, Weill J, Delestret I, et al.: Craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic obesity in children. Childs Nerv Syst 25 (3): 347-52, 2009.

-

Dolson EP, Conklin HM, Li C, et al.: Predicting behavioral problems in craniopharyngioma survivors after conformal radiation therapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 52 (7): 860-4, 2009.

-

Kawamata T, Amano K, Aihara Y, et al.: Optimal treatment strategy for craniopharyngiomas based on long-term functional outcomes of recent and past treatment modalities. Neurosurg Rev 33 (1): 71-81, 2010.

-

Holmer H, Ekman B, Björk J, et al.: Hypothalamic involvement predicts cardiovascular risk in adults with childhood onset craniopharyngioma on long-term GH therapy. Eur J Endocrinol 161 (5): 671-9, 2009.

-

Elowe-Gruau E, Beltrand J, Brauner R, et al.: Childhood craniopharyngioma: hypothalamus-sparing surgery decreases the risk of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98 (6): 2376-82, 2013.

-

Hoffmann A, Bootsveld K, Gebhardt U, et al.: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and fatigue in long-term survivors of childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. Eur J Endocrinol 173 (3): 389-97, 2015.

-

Kiehna EN, Merchant TE: Radiation therapy for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E10, 2010.

-

Lo AC, Howard AF, Nichol A, et al.: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study of Cerebrovascular Disease and Late Effects After Radiation Therapy for Craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63 (5): 786-93, 2016.

Changes to This Summary (06 / 02 / 2017)The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above. Editorial changes were made to this summary. This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® - NCI's Comprehensive Cancer Database pages. About This PDQ SummaryPurpose of This Summary This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians who care for cancer patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions. Reviewers and Updates This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should: - be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary. The lead reviewers for Childhood Craniopharyngioma Treatment are: - Kenneth J. Cohen, MD, MBA (Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins Hospital)

- Karen J. Marcus, MD (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children's Hospital)

- Roger J. Packer, MD (Children's National Health System)

- Malcolm A. Smith, MD, PhD (National Cancer Institute)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries. Levels of Evidence Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations. Permission to Use This Summary PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]." The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is: PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Craniopharyngioma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/brain/hp/child-cranio-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389330] Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images. Disclaimer Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page. Contact Us More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us. Last Revised: 2017-06-02 Last modified on: 8 September 2017

|

|