Genetics of Breast and Gynecologic Cancers (PDQ®): Genetics - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Genetics of Breast and Gynecologic Cancers (PDQ®): Genetics - Health Professional Information [NCI]Skip to the navigationExecutive SummaryThis executive summary reviews the topics covered in this PDQ summary on the genetics of breast and gynecologic cancers, with hyperlinks to detailed sections below that describe the evidence on each topic. - Inheritance and Risk

Factors suggestive of a genetic contribution to both breast cancer and gynecologic cancer include 1) an increased incidence of these cancers among individuals with a family history of these cancers; 2) multiple family members affected with these and other cancers; and 3) a pattern of cancers compatible with autosomal dominant inheritance. Both males and females can inherit and transmit an autosomal dominant cancer predisposition gene. Additional factors coupled with family history-such as reproductive history, oral contraceptive and hormone replacement use, radiation exposure early in life, alcohol consumption, and physical activity -can influence an individual's risk of developing cancer. Risk assessment models have been developed to clarify an individual's 1) lifetime risk of developing breast and/or gynecologic cancer; 2) likelihood of having a pathogenic variant in BRCA1 or BRCA2; and 3) likelihood of having a pathogenic variant in one of the mismatch repair genes associated with Lynch syndrome.

- Associated Genes and Syndromes

Breast and ovarian cancer are present in several autosomal dominant cancer syndromes, although they are most strongly associated with highly penetrant germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Other genes, such as PALB2, TP53 (associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome), PTEN (associated with Cowden syndrome), CDH1 (associated with diffuse gastric and lobular breast cancer syndrome), and STK11 (associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome), confer a risk to either or both of these cancers with relatively high penetrance. Inherited endometrial cancer is most commonly associated with Lynch syndrome, a condition caused by inherited pathogenic variants in the highly penetrant mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM. Colorectal cancer (and, to a lesser extent, ovarian cancer and stomach cancer) is also associated with Lynch syndrome. Additional genes, such as CHEK2, BRIP1, RAD51, and ATM, are associated with breast and/or gynecologic cancers with moderate penetrance. Genome-wide searches are showing promise in identifying common, low-penetrance susceptibility alleles for many complex diseases, including breast and gynecologic cancers, but the clinical utility of these findings remains uncertain.

- Clinical Management

Breast cancer screening strategies, including breast magnetic resonance imaging and mammography, are commonly performed in carriers of BRCA pathogenic variants and in individuals at increased risk of breast cancer. Initiation of screening is generally recommended at earlier ages and at more frequent intervals in individuals with an increased risk due to genetics and family history than in the general population. There is evidence to demonstrate that these strategies have utility in early detection of cancer. In contrast, there is currently no evidence to demonstrate that gynecologic cancer screening using cancer antigen 125 testing and transvaginal ultrasound leads to early detection of cancer. Risk-reducing surgeries, including risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM) and risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO), have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer and improve overall survival in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. Chemoprevention strategies, including the use of tamoxifen and oral contraceptives, have also been examined in this population. Tamoxifen use has been shown to reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants after treatment for breast cancer, but there are limited data in the primary cancer prevention setting to suggest that it reduces the risk of breast cancer among healthy female carriers of BRCA2 pathogenic variants. The use of oral contraceptives has been associated with a protective effect on the risk of developing ovarian cancer, including in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants, with no association of increased risk of breast cancer when using formulations developed after 1975.

- Psychosocial and Behavioral Issues

Psychosocial factors influence decisions about genetic testing for inherited cancer risk and risk-management strategies. Uptake of genetic testing varies widely across studies. Psychological factors that have been associated with testing uptake include cancer-specific distress and perceived risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer. Studies have shown low levels of distress after genetic testing for both carriers and noncarriers, particularly in the longer term. Uptake of RRM and RRSO also varies across studies, and may be influenced by factors such as cancer history, age, family history, recommendations of the health care provider, and pretreatment genetic education and counseling. Patients' communication with their family members about an inherited risk of breast and gynecologic cancer is complex; gender, age, and the degree of relatedness are some elements that affect disclosure of this information. Research is ongoing to better understand and address psychosocial and behavioral issues in high-risk families.

IntroductionGeneral Information Many of the medical and scientific terms used in this summary are found in the NCI Dictionary of Genetics Terms. When a linked term is clicked, the definition will appear in a separate window. A concerted effort is being made within the genetics community to shift terminology used to describe genetic variation. The shift is to use the term "variant" rather than the term "mutation" to describe a genetic difference that exists between the person or group being studied and the reference sequence. Variants can then be further classified as benign (harmless), likely benign, of uncertain significance, likely pathogenic, or pathogenic (disease causing). Throughout this summary, we will use the term pathogenic variant to describe a disease-causing mutation. Refer to the Cancer Genetics Overview summary for more information about variant classification. Many of the genes and conditions described in this summary are found in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. When OMIM appears after a gene name or the name of a condition, click on OMIM for a link to more information. Among women in the United States, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer after nonmelanoma skin cancer, and it is the second leading cause of cancer deaths after lung cancer. In 2017, an estimated 255,180 new cases of breast cancer (including 2,470 cases in men) will be diagnosed, and 41,070 deaths (including 460 deaths in men) will occur.[1] The incidence of breast cancer, particularly for estrogen receptor (ER)-positive cancers occurring after age 50 years, is declining and has declined at a faster rate since 2003; this may be temporally related to a decrease in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after early reports from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI).[2] An estimated 22,440 new cases of ovarian cancer are expected in the United States in 2017, with an estimated 14,080 deaths. Ovarian cancer is the fifth most deadly cancer in women.[1] An estimated 61,380 new cases of endometrial cancer are expected in the United States in 2017, with an estimated 10,920 deaths.[1] (Refer to the PDQ summaries on Breast Cancer Treatment; Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer Treatment; and Endometrial Cancer Treatment for more information about breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer rates, diagnosis, and management.) A possible genetic contribution to both breast and ovarian cancer risk is indicated by the increased incidence of these cancers among women with a family history (refer to the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer, Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer, and Risk Factors for Endometrial Cancer sections below for more information), and by the observation of some families in which multiple family members are affected with breast and/or ovarian cancer, in a pattern compatible with an inheritance of autosomal dominant cancer susceptibility. Formal studies of families (linkage analysis) have subsequently proven the existence of autosomal dominant predispositions to breast and ovarian cancer and have led to the identification of several highly penetrant genes as the cause of inherited cancer risk in many families. (Refer to the PDQ summary Cancer Genetics Overview for more information about linkage analysis.) Pathogenic variants in these genes are rare in the general population and are estimated to account for no more than 5% to 10% of breast and ovarian cancer cases overall. It is likely that other genetic factors contribute to the etiology of some of these cancers. Risk Factors for Breast Cancer Refer to the PDQ summary on Breast Cancer Prevention for information about risk factors for breast cancer in the general population. Age The cumulative risk of breast cancer increases with age, with most breast cancers occurring after age 50 years.[3] Breast cancer (and ovarian cancer, to a lesser degree) tends to occur at an earlier age in women with a genetic susceptibility than it does in women with sporadic cases. Family history including inherited cancer genes In cross-sectional studies of adult populations, 5% to 10% of women have a mother or sister with breast cancer, and about twice as many have either a first-degree relative (FDR) or a second-degree relative with breast cancer.[4,5,6,7] The risk conferred by a family history of breast cancer has been assessed in case-control and cohort studies, using volunteer and population-based samples, with generally consistent results.[8] In a pooled analysis of 38 studies, the relative risk (RR) of breast cancer conferred by an FDR with breast cancer was 2.1 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.0-2.2).[8] Risk increases with the number of affected relatives, age at diagnosis, the occurrence of bilateral or multiple ipsilateral breast cancers in a family member, and the number of affected male relatives.[5,6,8,9,10] A large population-based study from the Swedish Family Cancer Database confirmed the finding of a significantly increased risk of breast cancer in women who had a mother or a sister with breast cancer. The hazard ratio (HR) for women with a single breast cancer in the family was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.8-1.9) and was 2.7 (95% CI, 2.6-2.9) for women with a family history of multiple breast cancers. For women who had multiple breast cancers in the family, with one occurring before age 40 years, the HR was 3.8 (95% CI, 3.1-4.8). However, the study also found a significant increase in breast cancer risk if the relative was aged 60 years or older, suggesting that breast cancer at any age in the family carries some increase in risk.[10] One of the largest studies of twins ever conducted, with 80,309 monozygotic twins and 123,382 dizygotic twins, reported a heritability estimate for breast cancer of 31% (95% CI, 11%-51%).[11] If a monozygotic twin had breast cancer, her twin sister had a 28.1% probability of developing breast cancer (95% CI, 23.9%-32.8%), and if a dizygotic twin had breast cancer, her twin sister had a 19.9% probability of developing breast cancer (95% CI, 17%-23.2%). These estimates suggest a 10% higher risk of breast cancer for monozygotic twins than for dizygotic twins. However, a high rate of discordance even between monozygotic twins suggests that environmental factors also have a role in modifying breast cancer risk. (Refer to the Penetrance of BRCA pathogenic variants section of this summary for a discussion of familial risk in women from families with BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants who themselves test negative for the family pathogenic variant.) Reproductive history In general, breast cancer risk increases with early menarche and late menopause and is reduced by early first full-term pregnancy. There may be an increased risk of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants with pregnancy at a younger age (before age 30 years), with a more significant effect seen for carriers of BRCA1 pathogenic variants.[12,13,14] Likewise, breastfeeding can reduce breast cancer risk in carriers of BRCA1 (but not BRCA2) pathogenic variants.[15] Regarding the effect of pregnancy on breast cancer outcomes, neither diagnosis of breast cancer during pregnancy nor pregnancy after breast cancer seems to be associated with adverse survival outcomes in women who carry a BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant.[16] Parity appears to be protective for carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants, with an additional protective effect for live birth before age 40 years.[17] Reproductive history can also affect the risk of ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer. (Refer to the Reproductive History sections in the Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer and Risk Factors for Endometrial Cancer sections of this summary for more information.) Oral contraceptives Oral contraceptives (OCs) may produce a slight increase in breast cancer risk among long-term users, but this appears to be a short-term effect. In a meta-analysis of data from 54 studies, the risk of breast cancer associated with OC use did not vary in relationship to a family history of breast cancer.[18] OCs are sometimes recommended for ovarian cancer prevention in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. (Refer to the Oral Contraceptives section in the Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer section of this summary for more information.) Although the data are not entirely consistent, a meta-analysis concluded that there was no significant increased risk of breast cancer with OC use in carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants.[19] However, use of OCs formulated before 1975 was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (summary relative risk [SRR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.06-2.04).[19] (Refer to the Reproductive factors section in the Clinical Management of Carriers of BRCA Pathogenic Variants section of this summary for more information.) Hormone replacement therapy Data exist from both observational and randomized clinical trials regarding the association between postmenopausal HRT and breast cancer. A meta-analysis of data from 51 observational studies indicated a RR of breast cancer of 1.35 (95% CI, 1.21-1.49) for women who had used HRT for 5 or more years after menopause.[20] The WHI (NCT00000611), a randomized controlled trial of about 160,000 postmenopausal women, investigated the risks and benefits of HRT. The estrogen-plus-progestin arm of the study, in which more than 16,000 women were randomly assigned to receive combined HRT or placebo, was halted early because health risks exceeded benefits.[21,22] Adverse outcomes prompting closure included significant increase in both total (245 vs. 185 cases) and invasive (199 vs. 150 cases) breast cancers (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02-1.5, P < . 001) and increased risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, and pulmonary embolism. Similar findings were seen in the estrogen-progestin arm of the prospective observational Million Women's Study in the United Kingdom.[23] The risk of breast cancer was not elevated, however, in women randomly assigned to estrogen-only versus placebo in the WHI study (RR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.59-1.01). Eligibility for the estrogen-only arm of this study required hysterectomy, and 40% of these patients also had undergone oophorectomy, which potentially could have impacted breast cancer risk.[24] The association between HRT and breast cancer risk among women with a family history of breast cancer has not been consistent; some studies suggest risk is particularly elevated among women with a family history, while others have not found evidence for an interaction between these factors.[25,26,27,28,29,20] The increased risk of breast cancer associated with HRT use in the large meta-analysis did not differ significantly between subjects with and without a family history.[29] The WHI study has not reported analyses stratified on breast cancer family history, and subjects have not been systematically tested for BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants.[22] Short-term use of hormones for treatment of menopausal symptoms appears to confer little or no breast cancer risk.[20,30] The effect of HRT on breast cancer risk among carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants has been studied in the context of bilateral risk-reducing oophorectomy, in which short-term replacement does not appear to reduce the protective effect of oophorectomy on breast cancer risk.[31] (Refer to the Hormone replacement therapy in carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants section of this summary for more information.) Hormone use can also affect the risk of developing endometrial cancer. (Refer to the Hormones section in the Risk Factors for Endometrial Cancer section of this summary for more information.) Radiation exposure Observations in survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and in women who have received therapeutic radiation treatments to the chest and upper body document increased breast cancer risk as a result of radiation exposure. The significance of this risk factor in women with a genetic susceptibility to breast cancer is unclear. Preliminary data suggest that increased sensitivity to radiation could be a cause of cancer susceptibility in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants,[32,33,34,35] and in association with germline ATM and TP53 variants.[36,37] The possibility that genetic susceptibility to breast cancer occurs via a mechanism of radiation sensitivity raises questions about radiation exposure. It is possible that diagnostic radiation exposure, including mammography, poses more risk in genetically susceptible women than in women of average risk. Therapeutic radiation could also pose a carcinogenic risk. A cohort study of carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants treated with breast-conserving therapy, however, showed no evidence of increased radiation sensitivity or sequelae in the breast, lung, or bone marrow of carriers.[38] This finding was confirmed in a retrospective cohort study of 691 patients with BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer who were followed up for a median of 8.6 years. No association between receiving adjuvant radiation therapy and increased risk of contralateral breast cancer was observed in the entire cohort, including the subset of patients younger than 40 years at primary breast cancer diagnosis.[39] Conversely, radiation sensitivity could make tumors in women with genetic susceptibility to breast cancer more responsive to radiation treatment. Studies examining the impact of radiation exposure, including, but not limited to, mammography, in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants have had conflicting results.[40,41,42,43,44,45] A large European study showed a dose-response relationship of increased risk with total radiation exposure, but this was primarily driven by nonmammographic radiation exposure before age 20 years.[44] Subsequently, no significant association was observed between prior mammography exposure and breast cancer risk in a prospective study of 1,844 BRCA1 carriers and 502 BRCA2 carriers without a breast cancer diagnosis at time of study entry; average follow-up time was 5.3 years.[45] (Refer to the Mammography section in the Clinical Management of Carriers of BRCA Pathogenic Variants section of this summary for more information about radiation.) Alcohol intake The risk of breast cancer increases by approximately 10% for each 10 g of daily alcohol intake (approximately one drink or less) in the general population.[46,47] Prior studies of carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants have found no increased risk associated with alcohol consumption.[48,49,50] Physical activity and anthropometry Weight gain and being overweight are commonly recognized risk factors for breast cancer. In general, overweight women are most commonly observed to be at increased risk of postmenopausal breast cancer and at reduced risk of premenopausal breast cancer. Sedentary lifestyle may also be a risk factor.[51] These factors have not been systematically evaluated in women with a positive family history of breast cancer or in carriers of cancer-predisposing pathogenic variants, but one study suggested a reduced risk of cancer associated with exercise among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants.[52] Benign breast disease and mammographic density Benign breast disease (BBD) is a risk factor for breast cancer, independent of the effects of other major risk factors for breast cancer (age, age at menarche, age at first live birth, and family history of breast cancer).[53] There may also be an association between BBD and family history of breast cancer.[54] An increased risk of breast cancer has also been demonstrated for women who have increased density of breast tissue as assessed by mammogram,[53,55,56] and breast density is likely to have a genetic component in its etiology.[57,58,59] Other factors Other risk factors, including those that are only weakly associated with breast cancer and those that have been inconsistently associated with the disease in epidemiologic studies (e.g., cigarette smoking), may be important in women who are in specific genotypically defined subgroups. One study [60] found a reduced risk of breast cancer among carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants who smoked, but an expanded follow-up study failed to find an association.[61] Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer Refer to the PDQ summary on Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer Prevention for information about risk factors for ovarian cancer in the general population. Age Ovarian cancer incidence rises in a linear fashion from age 30 years to age 50 years and continues to increase, though at a slower rate, thereafter. Before age 30 years, the risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer is remote, even in hereditary cancer families.[62] Family history including inherited cancer genes Although reproductive, demographic, and lifestyle factors affect risk of ovarian cancer, the single greatest ovarian cancer risk factor is a family history of the disease. A large meta-analysis of 15 published studies estimated an odds ratio of 3.1 for the risk of ovarian cancer associated with at least one FDR with ovarian cancer.[63] Reproductive history Nulliparity is consistently associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer, including among carriers of BRCA/BRCA2 pathogenic variants, yet a meta-analysis identified a risk reduction only in women with four or more live births.[14] Risk may also be increased among women who have used fertility drugs, especially those who remain nulligravid.[64,65] Several studies have reported a risk reduction in ovarian cancer after OC use in carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants;[66,67,68] a risk reduction has also been shown after tubal ligation in BRCA1 carriers, with a statistically significant decreased risk of 22% to 80% after the procedure.[68,69] Breastfeeding for more than 12 months may also be associated with a reduction in ovarian cancer among carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants.[70] On the other hand, evidence is growing that the use of menopausal HRT is associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer, particularly in long-time users and users of sequential estrogen-progesterone schedules.[71,72,73,74] Surgical history Bilateral tubal ligation and hysterectomy are associated with reduced ovarian cancer risk,[64,75,76] including in carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants.[77] Ovarian cancer risk is reduced more than 90% in women with documented BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants who chose risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO). In this same population, risk-reducing oophorectomy also resulted in a nearly 50% reduction in the risk of subsequent breast cancer.[78,79] (Refer to the RRSO section of this summary for more information about these studies.) Oral contraceptives Use of OCs for 4 or more years is associated with an approximately 50% reduction in ovarian cancer risk in the general population.[64,80] A majority of, but not all, studies also support OCs being protective among carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants.[69,81,82,83,84] A meta-analysis of 18 studies including 13,627 carriers of BRCA pathogenic variants reported a significantly reduced risk of ovarian cancer (SRR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.75) associated with OC use.[19] (Refer to the Oral contraceptives section in the Chemoprevention section of this summary for more information.) Risk Factors for Endometrial Cancer Refer to the PDQ summary on Endometrial Cancer Prevention for information about risk factors for endometrial cancer in the general population. Age Age is an important risk factor for endometrial cancer. Most women with endometrial cancer are diagnosed after menopause. Only 15% of women are diagnosed with endometrial cancer before age 50 years, and fewer than 5% are diagnosed before age 40 years.[85] Women with Lynch syndrome tend to develop endometrial cancer at an earlier age, with the median age at diagnosis of 48 years.[86] Family history including inherited cancer genes Although the hyperestrogenic state is the most common predisposing factor for endometrial cancer, family history also plays a significant role in a woman's risk for disease. Approximately 3% to 5% of uterine cancer cases are attributable to a hereditary cause,[87] with the main hereditary endometrial cancer syndrome being Lynch syndrome, an autosomal dominant genetic condition with a population prevalence of 1 in 300 to 1 in 1,000 individuals.[88,89] (Refer to the Lynch Syndrome section in the PDQ summary on Genetics of Colorectal Cancer for more information.) Non-Lynch syndrome genes may also contribute to endometrial cancer risk. In an unselected endometrial cancer cohort undergoing multigene panel testing, approximately 3% of patients tested positive for a germline pathogenic variant in non-Lynch syndrome genes, including CHEK2, APC, ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, NBN, PTEN, and RAD51C.[90] Notably, patients with pathogenic variants in non-Lynch syndrome genes were more likely to have serous tumor histology than were patients without pathogenic variants. Furthermore, although the overall risk of endometrial cancer after RRSO was not increased among carriers of BRCA1 pathogenic variants, these patients seemed to have an increased risk of serous and serous-like endometrial cancer.[91] Reproductive history Reproductive factors such as multiparity, late menarche, and early menopause decrease the risk of endometrial cancer because of the lower cumulative exposure to estrogen and the higher relative exposure to progesterone.[92,93] Hormones Hormonal factors that increase the risk of type I endometrial cancer are better understood. All endometrial cancers share a predominance of estrogen relative to progesterone. Prolonged exposure to estrogen or unopposed estrogen increases the risk of endometrial cancer. Endogenous exposure to estrogen can result from obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, and nulliparity, while exogenous estrogen can result from taking unopposed estrogen or tamoxifen. Unopposed estrogen increases the risk of developing endometrial cancer by twofold to twentyfold, proportional to the duration of use.[94,95] Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, acts as an estrogen agonist on the endometrium while acting as an estrogen antagonist in breast tissue, and increases the risk of endometrial cancer.[96] In contrast, OCs, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, and combination estrogen-progesterone hormone replacement therapy all reduce the risk of endometrial cancer through the antiproliferative effect of progesterone acting on the endometrium.[97,98,99,100] Autosomal Dominant Inheritance of Breast and Gynecologic Cancer Predisposition Autosomal dominant inheritance of breast and gynecologic cancers is characterized by transmission of cancer predisposition from generation to generation, through either the mother's or the father's side of the family, with the following characteristics: - Inheritance risk of 50%. When a parent carries an autosomal dominant genetic predisposition, each child has a 50:50 chance of inheriting the predisposition. Although the risk of inheriting the predisposition is 50%, not everyone with the predisposition will develop cancer because of incomplete penetrance and/or gender-restricted or gender-related expression.

- Both males and females can inherit and transmit an autosomal dominant cancer predisposition. A male who inherits a cancer predisposition can still pass the altered gene on to his sons and daughters.

Breast and ovarian cancer are components of several autosomal dominant cancer syndromes. The syndromes most strongly associated with both cancers are the syndromes associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants. Breast cancer is also a common feature of Li-Fraumeni syndrome due to TP53 pathogenic variants and of Cowden syndrome due to PTEN pathogenic variants.[101] Other genetic syndromes that may include breast cancer as an associated feature include heterozygous carriers of the ataxia telangiectasia gene and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Ovarian cancer has also been associated with Lynch syndrome, basal cell nevus (Gorlin) syndrome (OMIM), and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (OMIM).[101] Lynch syndrome is mainly associated with colorectal cancer and endometrial cancer, although several studies have demonstrated that patients with Lynch syndrome are also at risk of developing transitional cell carcinoma of the ureters and renal pelvis; cancers of the stomach, small intestine, liver and biliary tract, brain, breast, prostate, and adrenal cortex; and sebaceous skin tumors (Muir-Torre syndrome).[102,103,104,105,106,107,108] Germline pathogenic variants in the genes responsible for these autosomal dominant cancer syndromes produce different clinical phenotypes of characteristic malignancies and, in some instances, associated nonmalignant abnormalities. The family characteristics that suggest hereditary cancer predisposition include the following: - Multiple cancers within a family.

- Cancers typically occur at an earlier age than in sporadic cases (defined as cases not associated with genetic risk).

- Two or more primary cancers in a single individual. These could be multiple primary cancers of the same type (e.g., bilateral breast cancer) or primary cancer of different types (e.g., breast cancer and ovarian cancer in the same individual or endometrial and colon cancer in the same individual).

- Cases of male breast cancer. The inheritance risk for autosomal dominant genetic conditions is 50% for both males and females, but the differing penetrance of the genes may result in some unaffected individuals in the family.

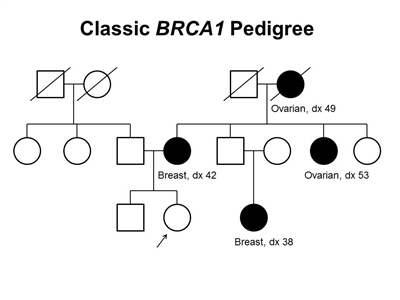

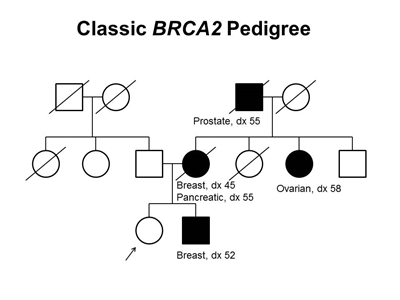

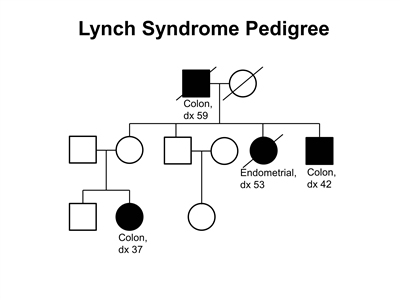

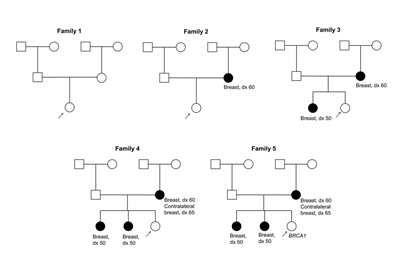

Figure 1 and Figure 2 depict some of the classic inheritance features of a BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant, respectively. Figure 3 depicts a classic family with Lynch syndrome. (Refer to the Standard Pedigree Nomenclature figure in the PDQ summary on Cancer Genetics Risk Assessment and Counseling for definitions of the standard symbols used in these pedigrees.)

Figure 1. BRCA1 pedigree. This pedigree shows some of the classic features of a family with a BRCA1 pathogenic variant across three generations, including affected family members with breast cancer or ovarian cancer and a young age at onset. BRCA1 families may exhibit some or all of these features. As an autosomal dominant syndrome, a BRCA1 pathogenic variant can be transmitted through maternal or paternal lineages, as depicted in the figure.

Figure 2. BRCA2 pedigree. This pedigree shows some of the classic features of a family with a BRCA2 pathogenic variant across three generations, including affected family members with breast (including male breast cancer), ovarian, pancreatic, or prostate cancers and a relatively young age at onset. BRCA2 families may exhibit some or all of these features. As an autosomal dominant syndrome, a BRCA2 pathogenic variant can be transmitted through maternal or paternal lineages, as depicted in the figure.

Figure 3. Lynch syndrome pedigree. This pedigree shows some of the classic features of a family with Lynch syndrome, including affected family members with colon cancer or endometrial cancer and a younger age at onset in some individuals. Lynch syndrome families may exhibit some or all of these features. Lynch syndrome families may also include individuals with other gastrointestinal, gynecologic, and genitourinary cancers, or other extracolonic cancers. As an autosomal dominant syndrome, Lynch syndrome can be transmitted through maternal or paternal lineages, as depicted in the figure.

There are no pathognomonic features distinguishing breast and ovarian cancers occurring in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants from those occurring in noncarriers. Breast cancers occurring in carriers of BRCA1 pathogenic variants are more likely to be ER-negative, progesterone receptor-negative, HER2/neu receptor-negative (i.e., triple-negative breast cancers), and have a basal phenotype. BRCA1-associated ovarian cancers are more likely to be high-grade and of serous histopathology. (Refer to the Pathology of breast cancer and Pathology of ovarian cancer sections of this summary for more information.) Some pathologic features distinguish carriers of Lynch syndrome-associated pathogenic variants from noncarriers. The hallmark feature of endometrial cancers occurring in Lynch syndrome is mismatch repair (MMR) defects, including the presence of microsatellite instability (MSI), and the absence of specific MMR proteins. In addition to these molecular changes, there are also histologic changes including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, peritumoral lymphocytes, undifferentiated tumor histology, lower uterine segment origin, and synchronous tumors. Considerations in Risk Assessment and in Identifying a Family History of Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk The accuracy and completeness of family histories must be taken into account when they are used to assess risk. A reported family history may be erroneous, or a person may be unaware of relatives affected with cancer. In addition, small family sizes and premature deaths may limit the information obtained from a family history. Breast or ovarian cancer on the paternal side of the family usually involves more distant relatives than does breast or ovarian cancer on the maternal side, so information may be more difficult to obtain. When self-reported information is compared with independently verified cases, the sensitivity of a history of breast cancer is relatively high, at 83% to 97%, but lower for ovarian cancer, at 60%.[109,110] Additional limitations of relying on family histories include adoption; families with a small number of women; limited access to family history information; and incidental removal of the uterus, ovaries, and/or fallopian tubes for noncancer indications. Family histories will evolve, therefore it is important to update family histories from both parents over time. (Refer to the Accuracy of the family history section in the PDQ summary on Cancer Genetics Risk Assessment and Counseling for more information.) Models for Prediction of Breast and Gynecologic Cancer Risk Models to predict an individual's lifetime risk of developing breast and/or gynecologic cancer are available.[111,112,113,114] In addition, models exist to predict an individual's likelihood of having a pathogenic variant in BRCA1, BRCA2, or one of the MMR genes associated with Lynch syndrome. (Refer to the Models for prediction of the likelihood of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant section of this summary for more information about some of these models.) Not all models can be appropriately applied to all patients. Each model is appropriate only when the patient's characteristics and family history are similar to those of the study population on which the model was based. Different models may provide widely varying risk estimates for the same clinical scenario, and the validation of these estimates has not been performed for many models.[112,115,116] Breast cancer risk assessment models In general, breast cancer risk assessment models are designed for two types of populations: 1) women without a pathogenic variant or strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer; and 2) women at higher risk because of a personal or family history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer.[116] Models designed for women of the first type (e.g., the Gail model, which is the basis for the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool [BCRAT]) [117], and the Colditz and Rosner model [118]) require only limited information about family history (e.g., number of FDRs with breast cancer). Models designed for women at higher risk require more detailed information about personal and family cancer history of breast and ovarian cancers, including ages at onset of cancer and/or carrier status of specific breast cancer-susceptibility alleles. The genetic factors used by the latter models differ, with some assuming one risk locus (e.g., the Claus model [119]), others assuming two loci (e.g., the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study [IBIS] model [120] and the BRCAPRO model [121]), and still others assuming an additional polygenic component in addition to multiple loci (e.g., the Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm [BOADICEA] model [122,123,124]). The models also differ in whether they include information about nongenetic risk factors. Three models (Gail/BCRAT, Pfeiffer,[114] and IBIS) include nongenetic risk factors but differ in the risk factors they include (e.g., the Pfeiffer model includes alcohol consumption, whereas the Gail/BCRAT does not). These models have limited ability to discriminate between individuals who are affected and those who are unaffected with cancer; a model with high discrimination would be close to 1, and a model with little discrimination would be close to 0.5; the discrimination of the models currently ranges between 0.56 and 0.63).[125] The existing models generally are more accurate in prospective studies that have assessed how well they predict future cancers.[116,126,127,128] In the United States, BRCAPRO, the Claus model,[119,129] and the Gail/BCRAT [117] are widely used in clinical counseling. Risk estimates derived from the models differ for an individual patient. Several other models that include more detailed family history information are also in use and are discussed below. Additional considerations for clinical use of breast cancer risk assessment models The Gail model is the basis for the BCRAT, a computer program available from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) by calling the Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237). This version of the Gail model estimates only the risk of invasive breast cancer. The Gail/BCRAT model has been found to be reasonably accurate at predicting breast cancer risk in large groups of white women who undergo annual screening mammography; however, reliability varies depending on the cohort studied.[130,131,132,133,134,135] Risk can be overestimated in the following populations: - Women who do not adhere to screening recommendations.[130,131]

- Women in the highest-risk strata.[133]

The Gail/BCRAT model is valid for women aged 35 years and older. The model was primarily developed for white women.[134] Extensions of the Gail model for African American women have been subsequently developed to calibrate risk estimates using data from more than 1,600 African American women with invasive breast cancer and more than 1,600 controls.[136] Additionally, extensions of the Gail model have incorporated high-risk single nucleotide polymorphisms and pathogenic variants; however, no software exists to calculate risk in these extended models.[137,138] Other risk assessment models incorporating breast density have been developed but are not ready for clinical use.[139,140] Generally, the Gail/BCRAT model should not be the sole model used for families with one or more of the following characteristics: - Multiple affected individuals with breast cancer or ovarian cancer (especially when one or more breast cancers are diagnosed before age 50 years).

- A woman with both breast and ovarian cancer.

- Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry with at least one case of breast or ovarian cancer (as these families are more likely to have a hereditary cancer susceptibility syndrome).

Commonly used models that incorporate family history include the IBIS, BOADICEA, and BRCAPRO models. The IBIS/Tyrer-Cuzick model incorporates both genetic and nongenetic factors.[120] A three-generation pedigree is used to estimate the likelihood that an individual carries either a BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variant or a hypothetical low-penetrance gene. In addition, the model incorporates personal risk factors such as parity, body mass index (BMI); height; and age at menarche, first live birth, menopause, and HRT use. Both genetic and nongenetic factors are combined to develop a risk estimate. The BOADICEA model examines family history to estimate breast cancer risk and also incorporates both BRCA1/BRCA2 and non-BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic risk factors.[123] The most important difference between BOADICEA and the other models using information on BRCA1/BRCA2 is that BOADICEA assumes an additional polygenic component in addition to multiple loci,[122,123,124] which is more in line with what is known about the underlying genetics of breast cancer. The BOADICEA model has also been expanded to include additional pathogenic variants, including CHEK2, ATM, and PALB2.[141] However, the discrimination and calibration for these models differ significantly when compared in independent samples;[126] the IBIS and BOADICEA models are more comparable when estimating risk over a shorter fixed time horizon (e.g., 10 years),[126] than when estimating remaining lifetime risk. As all risk assessment models for cancers are typically validated over a shorter time horizon (e.g., 5 or 10 years), fixed time horizon estimates rather than remaining lifetime risk may be more accurate and useful measures to convey in a clinical setting. In addition, readily available models that provide information about an individual woman's risk in relation to the population-level risk depending on her risk factors may be useful in a clinical setting (e.g., Your Disease Risk). Although this tool was developed using information about average-risk women and does not calculate absolute risk estimates, it still may be useful when counseling women about prevention. Risk assessment models are being developed and validated in large cohorts to integrate genetic and nongenetic data, breast density, and other biomarkers. Ovarian cancer risk assessment models Two risk prediction models have been developed for ovarian cancer.[113,114] The Rosner model [113] included age at menopause, age at menarche, oral contraception use, and tubal ligation; the concordance statistic was 0.60 (0.57-0.62). The Pfeiffer model [114] included oral contraceptive use, menopausal hormone therapy use, and family history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer, with a similar discriminatory power of 0.59 (0.56-0.62). Although both models were well calibrated, their modest discriminatory power limited their screening potential. Endometrial cancer risk assessment models The Pfeiffer model has been used to predict endometrial cancer risk in the general population.[114] For endometrial cancer, the relative risk model included BMI, menopausal hormone therapy use, menopausal status, age at menopause, smoking status, and OC use. The discriminatory power of the model was 0.68 (0.66-0.70); it overestimated observed endometrial cancers in most subgroups but underestimated disease in women with the highest BMI category, in premenopausal women, and in women taking menopausal hormone therapy for 10 years or more. In contrast, MMRpredict, PREMM1,2,6, and MMRpro are three quantitative predictive models used to identify individuals who may potentially have Lynch syndrome.[142,143,144] MMRpredict incorporates only colorectal cancer patients but does include MSI and immunohistochemistry (IHC) tumor testing results. PREMM1,2,6 accounts for other Lynch syndrome-associated tumors but does not include tumor testing results. MMRpro incorporates tumor testing and germline testing results, but is more time intensive because it includes affected and unaffected individuals in the risk-quantification process. All three predictive models are comparable to the traditional Amsterdam and Bethesda criteria in identifying individuals with colorectal cancer who carry MMR gene pathogenic variants.[145] However, because these models were developed and validated in colorectal cancer patients, the discriminative abilities of these models to identify Lynch syndrome are lower among individuals with endometrial cancer than among those with colon cancer.[146] In fact, the sensitivity and specificity of MSI and IHC in identifying carriers of pathogenic variants are considerably higher than the prediction models and support the use of molecular tumor testing to screen for Lynch syndrome in women with endometrial cancer. Table 1 summarizes salient aspects of breast and gynecologic cancer risk assessment models that are commonly used in the clinical setting. These models differ by the extent of family history included, whether nongenetic risk factors are included, and whether carrier status and polygenic risk are included (inputs to the models). The models also differ in the type of risk estimates that are generated (outputs of the models). These factors may be relevant in choosing the model that best applies to a particular individual. Table 1. Summary of Prediction Models Used to Calculate Age-Specific Absolute Risks of Breast and Gynecologic Cancers| Model | Family History (input) | Pathogenic Variants (input) | Risk Factors (input) | Risk Estimate Generated (output) |

|---|

| Refer toNCI's Cancer Risk Prediction and Assessmentwebsite for more information about available models. | | BCRAT = Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; BOADICEA = Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm; IBIS = International Breast Cancer Intervention Study. | | a High risk is defined as those with a personal or family history of the designated cancer type. | | b Takes into account polygenes as an underlying assumption of the model. | | Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Models | | Models for Average-Risk Women | | Gail/BCRAT | First-degree relatives (breast cancer) | No | Yes | Breast cancer | | Pfeiffer (breast)[114] | First-degree relatives (breast, ovarian cancers) | No | Yes | Breast cancer | | Colditz and Rosner[118] | None | No | Yes | Breast cancer | | Models for High-Risk Womena | | Claus[119] | Multigenerational (breast cancer) | No | No | Breast cancer | | BRCAPRO | Multigenerational (breast, ovarian cancers) | BRCA1/2 | No | Breast cancer; % risk of carryingBRCA1/2pathogenic variant | | IBIS | Multigenerational (ovarian cancer) | BRCA1/2 | Yes | Breast cancer; % risk of carryingBRCA1/2pathogenic variant | | BOADICEAb | Multigenerational (pancreatic, breast, ovarian cancers) | BRCA1/2 | No | Breast and ovarian cancer; % risk of carryingBRCA1/2pathogenic variant | | Ovarian Cancer Risk Assessment Models | | Models for Average-Risk Women | | Rosner[113] | None | No | Yes | Ovarian cancer | | Pfeiffer (ovarian)[114] | First-degree relatives (breast, ovarian cancers) | No | Yes | Breast cancer | | Models for High-Risk Womena | | BOADICEAb | Multigenerational (pancreatic, breast, ovarian cancers) | BRCA1/2 | No | Breast and ovarian cancer; % risk of carryingBRCA1/2pathogenic variant | | Endometrial Cancer Risk Assessment Models | | Models for Average-Risk Women | | Pfeiffer (endometrial)[114] | None | No | Yes | Endometrial cancer | | Models for High-Risk Womena | | PREMM(1,2,6) | Multigenerational (colon, endometrial and other Lynch syndrome-associated cancers and polyps) | No | No | % risk of carryingMLH1,MSH2,MSH6pathogenic variant | | MMRpro | Multigenerational (colon, endometrial cancers) | No | No | % risk of carryingMLH1,MSH2,MSH6pathogenic variant | | MMRpredict[142] | Multigenerational (colon, endometrial cancers) | No | No | % risk of carryingMLH1,MSH2,MSH6pathogenic variant | References:

-

American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2017. Atlanta, Ga: American Cancer Society, 2017. Available online. Last accessed May 25, 2017.

-

Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, et al.: The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med 356 (16): 1670-4, 2007.

-

Feuer EJ, Wun LM, Boring CC, et al.: The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 85 (11): 892-7, 1993.

-

Yang Q, Khoury MJ, Rodriguez C, et al.: Family history score as a predictor of breast cancer mortality: prospective data from the Cancer Prevention Study II, United States, 1982-1991. Am J Epidemiol 147 (7): 652-9, 1998.

-

Colditz GA, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, et al.: Family history, age, and risk of breast cancer. Prospective data from the Nurses' Health Study. JAMA 270 (3): 338-43, 1993.

-

Slattery ML, Kerber RA: A comprehensive evaluation of family history and breast cancer risk. The Utah Population Database. JAMA 270 (13): 1563-8, 1993.

-

Johnson N, Lancaster T, Fuller A, et al.: The prevalence of a family history of cancer in general practice. Fam Pract 12 (3): 287-9, 1995.

-

Pharoah PD, Day NE, Duffy S, et al.: Family history and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 71 (5): 800-9, 1997.

-

Bevier M, Sundquist K, Hemminki K: Risk of breast cancer in families of multiple affected women and men. Breast Cancer Res Treat 132 (2): 723-8, 2012.

-

Kharazmi E, Chen T, Narod S, et al.: Effect of multiplicity, laterality, and age at onset of breast cancer on familial risk of breast cancer: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 144 (1): 185-92, 2014.

-

Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, et al.: Familial Risk and Heritability of Cancer Among Twins in Nordic Countries. JAMA 315 (1): 68-76, 2016.

-

Johannsson O, Loman N, Borg A, et al.: Pregnancy-associated breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutation carriers. Lancet 352 (9137): 1359-60, 1998.

-

Jernström H, Lerman C, Ghadirian P, et al.: Pregnancy and risk of early breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Lancet 354 (9193): 1846-50, 1999.

-

Friebel TM, Domchek SM, Rebbeck TR: Modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 106 (6): dju091, 2014.

-

Jernström H, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, et al.: Breast-feeding and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 96 (14): 1094-8, 2004.

-

Valentini A, Lubinski J, Byrski T, et al.: The impact of pregnancy on breast cancer survival in women who carry a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat 142 (1): 177-85, 2013.

-

Milne RL, Osorio A, Ramón y Cajal T, et al.: Parity and the risk of breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 119 (1): 221-32, 2010.

-

Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet 347 (9017): 1713-27, 1996.

-

Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al.: Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 46 (12): 2275-84, 2010.

-

Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet 350 (9084): 1047-59, 1997.

-

Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators: Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288 (3): 321-33, 2002.

-

Chlebowski RT, Hendrix SL, Langer RD, et al.: Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Trial. JAMA 289 (24): 3243-53, 2003.

-

Beral V; Million Women Study Collaborators: Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 362 (9382): 419-27, 2003.

-

Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al.: Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291 (14): 1701-12, 2004.

-

Schuurman AG, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA: Exogenous hormone use and the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: results from The Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Causes Control 6 (5): 416-24, 1995.

-

Steinberg KK, Thacker SB, Smith SJ, et al.: A meta-analysis of the effect of estrogen replacement therapy on the risk of breast cancer. JAMA 265 (15): 1985-90, 1991.

-

Sellers TA, Mink PJ, Cerhan JR, et al.: The role of hormone replacement therapy in the risk for breast cancer and total mortality in women with a family history of breast cancer. Ann Intern Med 127 (11): 973-80, 1997.

-

Stanford JL, Weiss NS, Voigt LF, et al.: Combined estrogen and progestin hormone replacement therapy in relation to risk of breast cancer in middle-aged women. JAMA 274 (2): 137-42, 1995.

-

Colditz GA, Egan KM, Stampfer MJ: Hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: results from epidemiologic studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 168 (5): 1473-80, 1993.

-

Gorsky RD, Koplan JP, Peterson HB, et al.: Relative risks and benefits of long-term estrogen replacement therapy: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol 83 (2): 161-6, 1994.

-

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al.: Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol 23 (31): 7804-10, 2005.

-

Helzlsouer KJ, Harris EL, Parshad R, et al.: Familial clustering of breast cancer: possible interaction between DNA repair proficiency and radiation exposure in the development of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 64 (1): 14-7, 1995.

-

Helzlsouer KJ, Harris EL, Parshad R, et al.: DNA repair proficiency: potential susceptiblity factor for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 88 (11): 754-5, 1996.

-

Abbott DW, Thompson ME, Robinson-Benion C, et al.: BRCA1 expression restores radiation resistance in BRCA1-defective cancer cells through enhancement of transcription-coupled DNA repair. J Biol Chem 274 (26): 18808-12, 1999.

-

Abbott DW, Freeman ML, Holt JT: Double-strand break repair deficiency and radiation sensitivity in BRCA2 mutant cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 90 (13): 978-85, 1998.

-

Easton DF: Cancer risks in A-T heterozygotes. Int J Radiat Biol 66 (6 Suppl): S177-82, 1994.

-

Kleihues P, Schäuble B, zur Hausen A, et al.: Tumors associated with p53 germline mutations: a synopsis of 91 families. Am J Pathol 150 (1): 1-13, 1997.

-

Pierce LJ, Strawderman M, Narod SA, et al.: Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving treatment in women with breast cancer and germline BRCA1/2 mutations. J Clin Oncol 18 (19): 3360-9, 2000.

-

Drooger J, Akdeniz D, Pignol JP, et al.: Adjuvant radiotherapy for primary breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and risk of contralateral breast cancer with special attention to patients irradiated at younger age. Breast Cancer Res Treat 154 (1): 171-80, 2015.

-

Narod SA, Lubinski J, Ghadirian P, et al.: Screening mammography and risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol 7 (5): 402-6, 2006.

-

Andrieu N, Easton DF, Chang-Claude J, et al.: Effect of chest X-rays on the risk of breast cancer among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in the international BRCA1/2 carrier cohort study: a report from the EMBRACE, GENEPSO, GEO-HEBON, and IBCCS Collaborators' Group. J Clin Oncol 24 (21): 3361-6, 2006.

-

Goldfrank D, Chuai S, Bernstein JL, et al.: Effect of mammography on breast cancer risk in women with mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15 (11): 2311-3, 2006.

-

Gronwald J, Pijpe A, Byrski T, et al.: Early radiation exposures and BRCA1-associated breast cancer in young women from Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 112 (3): 581-4, 2008.

-

Pijpe A, Andrieu N, Easton DF, et al.: Exposure to diagnostic radiation and risk of breast cancer among carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations: retrospective cohort study (GENE-RAD-RISK). BMJ 345: e5660, 2012.

-

Giannakeas V, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al.: Mammography screening and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 147 (1): 113-8, 2014.

-

Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, et al.: Alcohol and breast cancer in women: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. JAMA 279 (7): 535-40, 1998.

-

Hamajima N, Hirose K, Tajima K, et al.: Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer--collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer 87 (11): 1234-45, 2002.

-

McGuire V, John EM, Felberg A, et al.: No increased risk of breast cancer associated with alcohol consumption among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations ages <50 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15 (8): 1565-7, 2006.

-

Dennis J, Ghadirian P, Little J, et al.: Alcohol consumption and the risk of breast cancer among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast 19 (6): 479-83, 2010.

-

Cybulski C, Lubinski J, Huzarski T, et al.: Prospective evaluation of alcohol consumption and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 151 (2): 435-41, 2015.

-

McTiernan A: Behavioral risk factors in breast cancer: can risk be modified? Oncologist 8 (4): 326-34, 2003.

-

King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB, et al.: Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science 302 (5645): 643-6, 2003.

-

Chen J, Pee D, Ayyagari R, et al.: Projecting absolute invasive breast cancer risk in white women with a model that includes mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst 98 (17): 1215-26, 2006.

-

Dupont WD, Page DL, Parl FF, et al.: Long-term risk of breast cancer in women with fibroadenoma. N Engl J Med 331 (1): 10-5, 1994.

-

Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, et al.: Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 87 (9): 670-5, 1995.

-

Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, et al.: Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: effects with time, age, and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst 87 (21): 1622-9, 1995.

-

Pankow JS, Vachon CM, Kuni CC, et al.: Genetic analysis of mammographic breast density in adult women: evidence of a gene effect. J Natl Cancer Inst 89 (8): 549-56, 1997.

-

Boyd NF, Lockwood GA, Martin LJ, et al.: Mammographic densities and risk of breast cancer among subjects with a family history of this disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 91 (16): 1404-8, 1999.

-

Vachon CM, King RA, Atwood LD, et al.: Preliminary sibpair linkage analysis of percent mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst 91 (20): 1778-9, 1999.

-

Brunet JS, Ghadirian P, Rebbeck TR, et al.: Effect of smoking on breast cancer in carriers of mutant BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. J Natl Cancer Inst 90 (10): 761-6, 1998.

-

Ghadirian P, Lubinski J, Lynch H, et al.: Smoking and the risk of breast cancer among carriers of BRCA mutations. Int J Cancer 110 (3): 413-6, 2004.

-

Amos CI, Struewing JP: Genetic epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer 71 (2 Suppl): 566-72, 1993.

-

Stratton JF, Pharoah P, Smith SK, et al.: A systematic review and meta-analysis of family history and risk of ovarian cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 105 (5): 493-9, 1998.

-

Whittemore AS, Harris R, Itnyre J: Characteristics relating to ovarian cancer risk: collaborative analysis of 12 US case-control studies. II. Invasive epithelial ovarian cancers in white women. Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Group. Am J Epidemiol 136 (10): 1184-203, 1992.

-

Brinton LA, Lamb EJ, Moghissi KS, et al.: Ovarian cancer risk after the use of ovulation-stimulating drugs. Obstet Gynecol 103 (6): 1194-203, 2004.

-

Gronwald J, Byrski T, Huzarski T, et al.: Influence of selected lifestyle factors on breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers from Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 95 (2): 105-9, 2006.

-

McLaughlin JR, Risch HA, Lubinski J, et al.: Reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol 8 (1): 26-34, 2007.

-

Antoniou AC, Rookus M, Andrieu N, et al.: Reproductive and hormonal factors, and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the International BRCA1/2 Carrier Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18 (2): 601-10, 2009.

-

Narod SA, Sun P, Ghadirian P, et al.: Tubal ligation and risk of ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: a case-control study. Lancet 357 (9267): 1467-70, 2001.

-

Kotsopoulos J, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al.: Factors influencing ovulation and the risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Int J Cancer 137 (5): 1136-46, 2015.

-

Rodriguez C, Patel AV, Calle EE, et al.: Estrogen replacement therapy and ovarian cancer mortality in a large prospective study of US women. JAMA 285 (11): 1460-5, 2001.

-

Riman T, Dickman PW, Nilsson S, et al.: Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer in Swedish women. J Natl Cancer Inst 94 (7): 497-504, 2002.

-

Lacey JV Jr, Mink PJ, Lubin JH, et al.: Menopausal hormone replacement therapy and risk of ovarian cancer. JAMA 288 (3): 334-41, 2002.

-

Anderson GL, Judd HL, Kaunitz AM, et al.: Effects of estrogen plus progestin on gynecologic cancers and associated diagnostic procedures: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA 290 (13): 1739-48, 2003.

-

Tortolero-Luna G, Mitchell MF: The epidemiology of ovarian cancer. J Cell Biochem Suppl 23: 200-7, 1995.

-

Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al.: Tubal ligation, hysterectomy, and risk of ovarian cancer. A prospective study. JAMA 270 (23): 2813-8, 1993.

-

Rutter JL, Wacholder S, Chetrit A, et al.: Gynecologic surgeries and risk of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 Ashkenazi founder mutations: an Israeli population-based case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 (14): 1072-8, 2003.

-

Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, et al.: Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med 346 (21): 1609-15, 2002.

-

Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, et al.: Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med 346 (21): 1616-22, 2002.

-

John EM, Whittemore AS, Harris R, et al.: Characteristics relating to ovarian cancer risk: collaborative analysis of seven U.S. case-control studies. Epithelial ovarian cancer in black women. Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 85 (2): 142-7, 1993.

-

Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, et al.: Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. N Engl J Med 339 (7): 424-8, 1998.

-

Whittemore AS, Balise RR, Pharoah PD, et al.: Oral contraceptive use and ovarian cancer risk among carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Br J Cancer 91 (11): 1911-5, 2004.

-

McGuire V, Felberg A, Mills M, et al.: Relation of contraceptive and reproductive history to ovarian cancer risk in carriers and noncarriers of BRCA1 gene mutations. Am J Epidemiol 160 (7): 613-8, 2004.

-

Modan B, Hartge P, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, et al.: Parity, oral contraceptives, and the risk of ovarian cancer among carriers and noncarriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med 345 (4): 235-40, 2001.

-

Soliman PT, Oh JC, Schmeler KM, et al.: Risk factors for young premenopausal women with endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 105 (3): 575-80, 2005.

-

Vasen HF, Stormorken A, Menko FH, et al.: MSH2 mutation carriers are at higher risk of cancer than MLH1 mutation carriers: a study of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer families. J Clin Oncol 19 (20): 4074-80, 2001.

-

Daniels MS: Genetic testing by cancer site: uterus. Cancer J 18 (4): 338-42, 2012 Jul-Aug.

-

Dunlop MG, Farrington SM, Nicholl I, et al.: Population carrier frequency of hMSH2 and hMLH1 mutations. Br J Cancer 83 (12): 1643-5, 2000.

-

de la Chapelle A: The incidence of Lynch syndrome. Fam Cancer 4 (3): 233-7, 2005.

-

Ring KL, Bruegl AS, Allen BA, et al.: Germline multi-gene hereditary cancer panel testing in an unselected endometrial cancer cohort. Mod Pathol 29 (11): 1381-1389, 2016.

-

Shu CA, Pike MC, Jotwani AR, et al.: Uterine Cancer After Risk-Reducing Salpingo-oophorectomy Without Hysterectomy in Women With BRCA Mutations. JAMA Oncol 2 (11): 1434-1440, 2016.

-

McPherson CP, Sellers TA, Potter JD, et al.: Reproductive factors and risk of endometrial cancer. The Iowa Women's Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 143 (12): 1195-202, 1996.

-

Dossus L, Allen N, Kaaks R, et al.: Reproductive risk factors and endometrial cancer: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer 127 (2): 442-51, 2010.

-

Shapiro S, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, et al.: Risk of localized and widespread endometrial cancer in relation to recent and discontinued use of conjugated estrogens. N Engl J Med 313 (16): 969-72, 1985.

-

Ziel HK, Finkle WD: Increased risk of endometrial carcinoma among users of conjugated estrogens. N Engl J Med 293 (23): 1167-70, 1975.

-

Fisher B, Costantino JP, Redmond CK, et al.: Endometrial cancer in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-14. J Natl Cancer Inst 86 (7): 527-37, 1994.

-

Pike MC, Peters RK, Cozen W, et al.: Estrogen-progestin replacement therapy and endometrial cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 89 (15): 1110-6, 1997.

-

Fournier A, Dossus L, Mesrine S, et al.: Risks of endometrial cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies in the E3N cohort, 1992-2008. Am J Epidemiol 180 (5): 508-17, 2014.

-

Weiss NS, Sayvetz TA: Incidence of endometrial cancer in relation to the use of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med 302 (10): 551-4, 1980.

-

Soini T, Hurskainen R, Grénman S, et al.: Cancer risk in women using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in Finland. Obstet Gynecol 124 (2 Pt 1): 292-9, 2014.

-

Lindor NM, McMaster ML, Lindor CJ, et al.: Concise handbook of familial cancer susceptibility syndromes - second edition. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr (38): 1-93, 2008.

-

Vasen HF, Offerhaus GJ, den Hartog Jager FC, et al.: The tumour spectrum in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: a study of 24 kindreds in the Netherlands. Int J Cancer 46 (1): 31-4, 1990.

-

Watson P, Lynch HT: Extracolonic cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer 71 (3): 677-85, 1993.

-

Watson P, Vasen HF, Mecklin JP, et al.: The risk of endometrial cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Am J Med 96 (6): 516-20, 1994.

-

Aarnio M, Mecklin JP, Aaltonen LA, et al.: Life-time risk of different cancers in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome. Int J Cancer 64 (6): 430-3, 1995.

-

Raymond VM, Everett JN, Furtado LV, et al.: Adrenocortical carcinoma is a lynch syndrome-associated cancer. J Clin Oncol 31 (24): 3012-8, 2013.

-

Raymond VM, Mukherjee B, Wang F, et al.: Elevated risk of prostate cancer among men with Lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol 31 (14): 1713-8, 2013.

-

Suspiro A, Fidalgo P, Cravo M, et al.: The Muir-Torre syndrome: a rare variant of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer associated with hMSH2 mutation. Am J Gastroenterol 93 (9): 1572-4, 1998.

-

Kerber RA, Slattery ML: Comparison of self-reported and database-linked family history of cancer data in a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 146 (3): 244-8, 1997.

-

Parent ME, Ghadirian P, Lacroix A, et al.: The reliability of recollections of family history: implications for the medical provider. J Cancer Educ 12 (2): 114-20, 1997 Summer.

-

Ready K, Litton JK, Arun BK: Clinical application of breast cancer risk assessment models. Future Oncol 6 (3): 355-65, 2010.

-

Amir E, Freedman OC, Seruga B, et al.: Assessing women at high risk of breast cancer: a review of risk assessment models. J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (10): 680-91, 2010.

-

Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Webb PM, et al.: Mathematical models of ovarian cancer incidence. Epidemiology 16 (4): 508-15, 2005.

-

Pfeiffer RM, Park Y, Kreimer AR, et al.: Risk prediction for breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer in white women aged 50 y or older: derivation and validation from population-based cohort studies. PLoS Med 10 (7): e1001492, 2013.

-

Gail MH, Mai PL: Comparing breast cancer risk assessment models. J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (10): 665-8, 2010.

-

Quante AS, Whittemore AS, Shriver T, et al.: Breast cancer risk assessment across the risk continuum: genetic and nongenetic risk factors contributing to differential model performance. Breast Cancer Res 14 (6): R144, 2012.

-

Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al.: Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 (24): 1879-86, 1989.

-

Colditz GA, Rosner B: Cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 70 years according to risk factor status: data from the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 152 (10): 950-64, 2000.

-

Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD: Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer 73 (3): 643-51, 1994.

-

Tyrer J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J: A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat Med 23 (7): 1111-30, 2004.

-

Parmigiani G, Berry D, Aguilar O: Determining carrier probabilities for breast cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet 62 (1): 145-58, 1998.

-

Antoniou AC, Pharoah PD, McMullan G, et al.: A comprehensive model for familial breast cancer incorporating BRCA1, BRCA2 and other genes. Br J Cancer 86 (1): 76-83, 2002.

-

Antoniou AC, Pharoah PP, Smith P, et al.: The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 91 (8): 1580-90, 2004.

-

Antoniou AC, Cunningham AP, Peto J, et al.: The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers: updates and extensions. Br J Cancer 98 (8): 1457-66, 2008.

-

Anothaisintawee T, Teerawattananon Y, Wiratkapun C, et al.: Risk prediction models of breast cancer: a systematic review of model performances. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133 (1): 1-10, 2012.

-

Amir E, Evans DG, Shenton A, et al.: Evaluation of breast cancer risk assessment packages in the family history evaluation and screening programme. J Med Genet 40 (11): 807-14, 2003.

-

Laitman Y, Simeonov M, Keinan-Boker L, et al.: Breast cancer risk prediction accuracy in Jewish Israeli high-risk women using the BOADICEA and IBIS risk models. Genet Res (Camb) 95 (6): 174-7, 2013.

-

MacInnis RJ, Bickerstaffe A, Apicella C, et al.: Prospective validation of the breast cancer risk prediction model BOADICEA and a batch-mode version BOADICEACentre. Br J Cancer 109 (5): 1296-301, 2013.

-

Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD: The calculation of breast cancer risk for women with a first degree family history of ovarian cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 28 (2): 115-20, 1993.

-

Bondy ML, Lustbader ED, Halabi S, et al.: Validation of a breast cancer risk assessment model in women with a positive family history. J Natl Cancer Inst 86 (8): 620-5, 1994.

-

Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Hunter D, et al.: Validation of the Gail et al. model for predicting individual breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 86 (8): 600-7, 1994.

-

Rockhill B, Spiegelman D, Byrne C, et al.: Validation of the Gail et al. model of breast cancer risk prediction and implications for chemoprevention. J Natl Cancer Inst 93 (5): 358-66, 2001.

-

Costantino JP, Gail MH, Pee D, et al.: Validation studies for models projecting the risk of invasive and total breast cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 91 (18): 1541-8, 1999.

-

Bondy ML, Newman LA: Breast cancer risk assessment models: applicability to African-American women. Cancer 97 (1 Suppl): 230-5, 2003.

-

Schonfeld SJ, Pee D, Greenlee RT, et al.: Effect of changing breast cancer incidence rates on the calibration of the Gail model. J Clin Oncol 28 (14): 2411-7, 2010.

-

Gail MH, Costantino JP, Pee D, et al.: Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in African American women. J Natl Cancer Inst 99 (23): 1782-92, 2007.

-

Gail MH: Discriminatory accuracy from single-nucleotide polymorphisms in models to predict breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 100 (14): 1037-41, 2008.

-

Gail MH: Value of adding single-nucleotide polymorphism genotypes to a breast cancer risk model. J Natl Cancer Inst 101 (13): 959-63, 2009.

-

Barlow WE, White E, Ballard-Barbash R, et al.: Prospective breast cancer risk prediction model for women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst 98 (17): 1204-14, 2006.

-

Tice JA, Cummings SR, Ziv E, et al.: Mammographic breast density and the Gail model for breast cancer risk prediction in a screening population. Breast Cancer Res Treat 94 (2): 115-22, 2005.

-

Lee AJ, Cunningham AP, Tischkowitz M, et al.: Incorporating truncating variants in PALB2, CHEK2, and ATM into the BOADICEA breast cancer risk model. Genet Med 18 (12): 1190-1198, 2016.

-

Barnetson RA, Tenesa A, Farrington SM, et al.: Identification and survival of carriers of mutations in DNA mismatch-repair genes in colon cancer. N Engl J Med 354 (26): 2751-63, 2006.

-

Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, Mercado R, et al.: The PREMM(1,2,6) model predicts risk of MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 germline mutations based on cancer history. Gastroenterology 140 (1): 73-81, 2011.

-

Chen S, Wang W, Lee S, et al.: Prediction of germline mutations and cancer risk in the Lynch syndrome. JAMA 296 (12): 1479-87, 2006.

-

Khan O, Blanco A, Conrad P, et al.: Performance of Lynch syndrome predictive models in a multi-center US referral population. Am J Gastroenterol 106 (10): 1822-7; quiz 1828, 2011.

-

Mercado RC, Hampel H, Kastrinos F, et al.: Performance of PREMM(1,2,6), MMRpredict, and MMRpro in detecting Lynch syndrome among endometrial cancer cases. Genet Med 14 (7): 670-80, 2012.

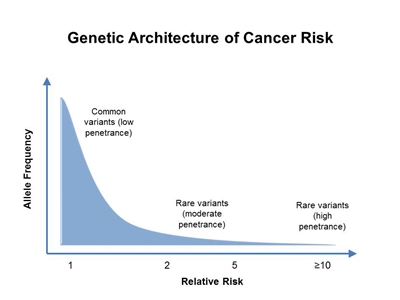

Penetrance of Inherited Susceptibility to Hereditary Breast and / or Gynecologic CancersThe proportion of individuals carrying a pathogenic variant who will manifest a certain disease is referred to as penetrance. In general, common genetic variants that are associated with cancer susceptibility have a lower penetrance than rare genetic variants. This is depicted in Figure 4. For adult-onset diseases, penetrance is usually described by the individual carrier's age, sex, and organ site. For example, the penetrance for breast cancer in female carriers of BRCA1 pathogenic variants is often quoted by age 50 years and by age 70 years. Of the numerous methods for estimating penetrance, none are without potential biases, and determining an individual carrier's risk of cancer involves some level of imprecision.

Figure 4. Genetic architecture of cancer risk. This graph depicts the general finding of a low relative risk associated with common, low-penetrance genetic variants, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified in genome-wide association studies, and a higher relative risk associated with rare, high-penetrance genetic variants, such as pathogenic variants in the BRCA1/BRCA2 genes associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and the mismatch repair genes associated with Lynch syndrome.